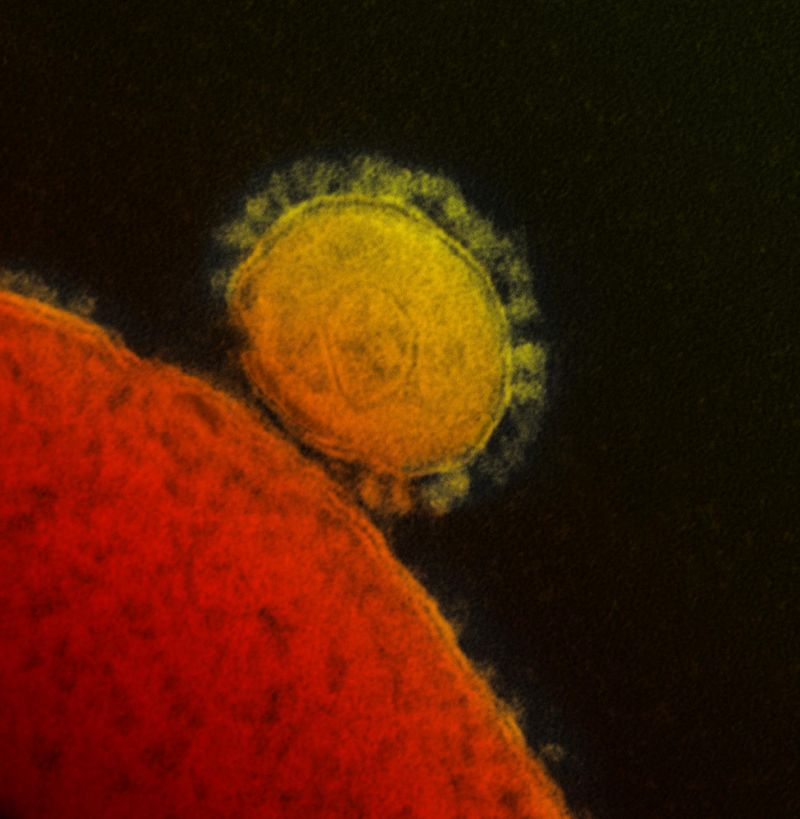

Researchers have just shown that pregnant female mice with low iron levels can lead to the development of male embryos that develop ovaries, regardless of their genetics. This discovery could have significant implications for our understanding of sex determination, and it’s thought to be the first time environmental factors have been documented to influence the process in mammals.

Sex in mammals is generally thought of as determined at the point when the sperm fertilizes the egg, but for a short while, the embryo exists in an undifferentiated state that is neither male nor female, as far as the gonads go. According to conventional interpretations, after this period, the embryo typically goes on to develop into either a male or female based on its genetics – if the embryo had a Y chromosome at conception, then it becomes male, if it had XX chromosomes, then it becomes female. However, "typically" does not mean "always".

Embryonic sex development is a complex process. You may have heard the idea that, at first, all embryos are female until later in their development. This isn’t exactly true. It’s an oversimplification of a more complicated state. In reality, during early development, the gonads of an embryo are undifferentiated, which means they are phenotypically female. However, slightly later in gestation, if the embryo has the Y chromosome, then it will start to express a gene that leads to changes that develop its testes.

That gene is SRY, which is found on the Y chromosome. It sends instructions that produce the sex-determining region Y protein, which helps in male-typical sex development (usually) following pre-determined patterns based on an individual’s chromosomes. It essentially leads the embryo to develop testes and prevents the development of female reproductive structures (ovaries, the uterus, etc). It also initiates the production of sex hormones and the activity of other genes involved in physical traits associated with each sex.

In mammals, this process takes place in the uterus, where, so we believed, environmental influences were minimal if not non-existent. However, this new research challenges this assumption.

The team found that if a mother mouse’s iron concentrations were reduced to a certain degree, then the SRY gene could, in some cases, become inactive. They demonstrated this with one set of experiments in which the team induced an iron deficiency in the mother mice by giving them a drug called oral iron chelator deferasirox (DFX). As a result, four out of 72 XY embryos developed two ovaries and another one ovary and one testis.

In another set of experiments, male embryos had their iron levels manipulated through an in vitro gonad culture. The team found that six out of 39 embryos with XY chromosomes were born with two ovaries. They also found that one mouse was born with one testis and one ovary.

These results illustrate that environmental factors such as iron levels can influence sexual development in mammals. Although the number of affected mice may seem small, it is enough to show that there is more than genetics at play in this process. It seems that very low iron levels influence the enzyme KDM3A, which usually modifies processes that turn off the SRY gene at the point where it should determine the mouse’s sex.

The results may well shift our understanding of how sex is determined, though it is still unclear whether the same conditions would produce the same changes in humans. Nevertheless, it shows that environmental factors are also at play in something that was long thought to be purely genetic.

The study is published in Nature.